During the socialist era of Czechoslovakia, Tuzex shops represented a special and curious part of everyday life. Established in 1957, Tuzex stores were government-run outlets where citizens could purchase Western and luxury goods—items otherwise unavailable in regular shops. From Levi's jeans and foreign chocolate to electronics and perfumes, Tuzex was a window to the West in an otherwise closed economy.

But there was a catch: you couldn’t pay with regular Czechoslovak koruna. Instead, you needed Tuzex bons, a special form of internal currency issued by the state.

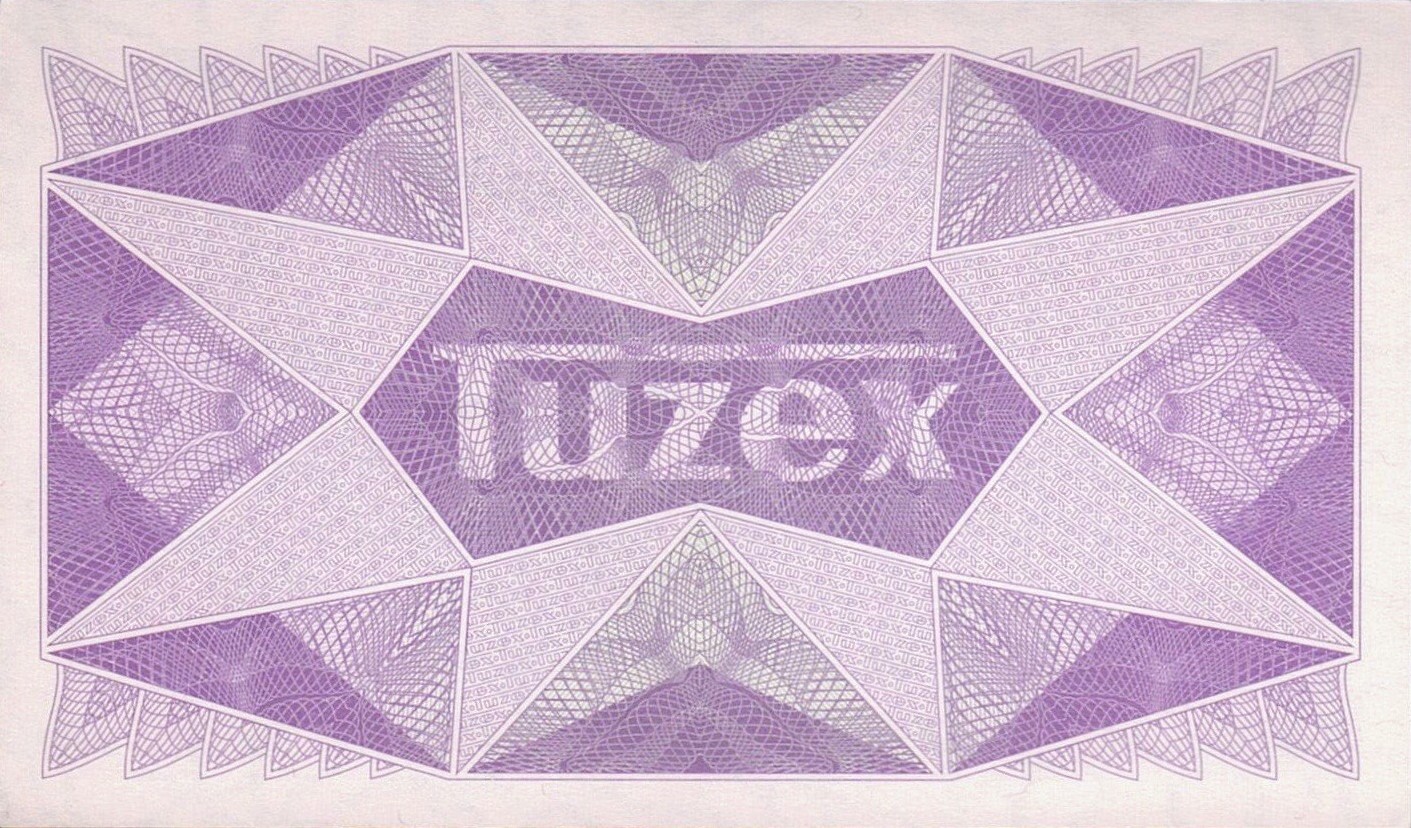

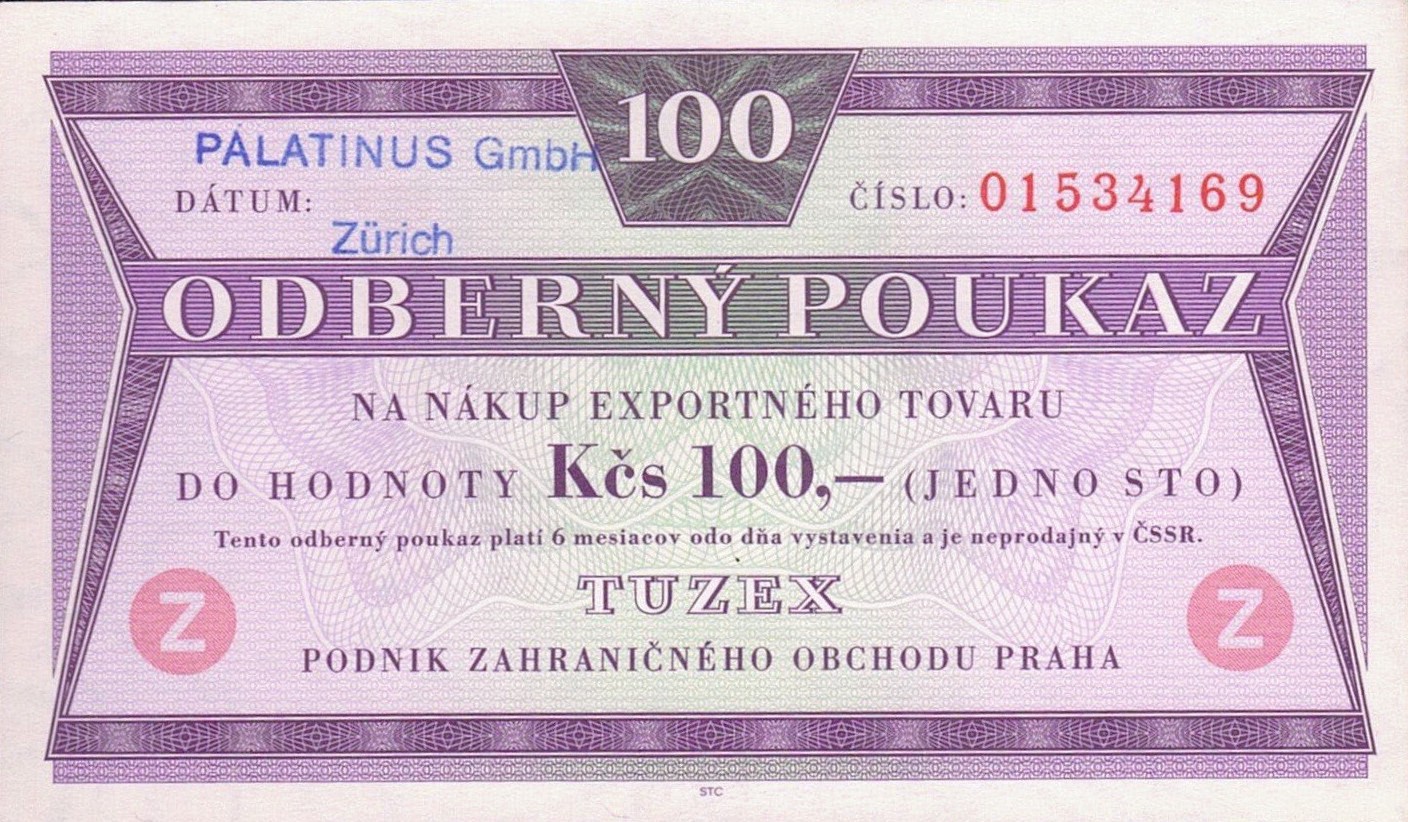

Tuzex bons were essentially vouchers—paper slips that acted as a substitute currency, only valid within Tuzex shops. These bons were typically bought with foreign hard currency, such as West German marks or U.S. dollars. Since most citizens didn’t have legal access to foreign currency, bons became a black market commodity, often traded for regular koruna at steep exchange rates.

This created a parallel economy, where people used bons not just to shop, but to signal wealth and status. Owning Western clothes or electronics from Tuzex was a symbol of prestige, especially among the youth.

Czechoslovakia Tuzex Bon 100 Korun 1973 – the highest denomination of bon used in Tuzex, UNC condition.

Today, Tuzex bons are a fascinating collectible—a reminder of the unique economic workarounds used during socialism. They offer insight into how controlled economies functioned and how citizens adapted to shortages and restrictions. Much like banknotes, Tuzex bons feature distinct designs and series, making them a niche interest among collectors of Czechoslovak currency and socialist memorabilia.

What was once a workaround to access Western goods has now become a symbol of a vanished era—part of the broader and endlessly intriguing world of Czechoslovak currency history.